written by Bonnie Gray and Dottie Murchison

revisions by Jeannette King, Mark Koscuiszka, Julie Housum, and Donna Vigue

Until the mid-1800s, the only way to arrive in Lincoln was to paddle up the Penobscot River, walk the ancient Indian footpaths while fording the streams, or trek beside ox-drawn wagons over river ice. More modern travelers had the option of driving up Route 2, along the river from Howland or down from Medway. Then in 1956 Interstate 95 expanded northward and, in 1971, a bridge was built across the Penobscot River, allowing Lincoln to have its own exit.

Lincoln’s early settlers must have possessed many characteristics that allowed them to survive and to prosper. They had to be people courageous and able enough (mentally and physically) to leave a place where their lives were established amidst family and friends—a place already labeled on a map—to arrive somewhere without these foundations and struggle to create them. They must have been tenacious, dogged, and determined—not just to persevere, but to thrive in uncharted territory.

That spirit of perseverance has echoed throughout Lincoln’s history. Without it, Lincoln would not be the successful town that exists today. That pioneer spirit has helped the citizens of Lincoln weather fires and floods, economic disasters, and the losses and changes that come to any town as it grows.

Fires in Lincoln

Fire has haunted towns and villages throughout history. In the late 1800’s buildings were constructed almost exclusively of wood and were often built close together. When one building caught fire, others generally became engulfed in flames. On June 21, 1887, Lincoln experienced fire’s destruction firsthand. The Whig and Courier, a Bangor newspaper, reported the event:

About half past ten o’clock last night a dispatch was received in this city for Mayor Bragg, announcing that the village of Lincoln was on fire and an engine was wanted from this city… the whole village was in danger of burning if help was not speedily had. The ringing of the Steamer bell called out the firemen and the Steamer with hose was loaded on a train… [t] he train left Bangor at ten minutes of twelve and arrived at Lincoln about quarter past one. A dispatch… announced that the Pinkham and Bennett’s stores and the Mansion House were entirely burned… the American Express Co. was also burned…

A day later the Whig and Courier gave a further report of the fire:

The fire was discovered in the store of M.B. Pinkham and had caught in the sheathing of the ceiling from a suspended kerosene oil lamp. The building was soon ablaze and in spite of great efforts but very few goods were saved. The town records and letters in the post office connected to the store were all saved without injury. The Mansion House caught soon after, being situated next to the Block and was soon a mass of ruins.

Plaisted Tannery Fire, Lincoln, 1899

Lincoln Historical Society

In 1889, E. A. Weatherbee purchased the two lots that had burned. Mr. Weatherbee owned and operated Weatherbee Hardware on the opposite side of the street. The store needed to expand, and Mr. Weatherbee saw the fire as an opportunity to help grow his business and restore a vital part of downtown Lincoln.

In January of 2002, Lincoln once again experienced fire’s devastation. A year later, the January 21, 2003, edition of the Bangor Daily News recalled the events. "Within a three-day span... two fires wiped out about twenty-five percent of Lincoln's downtown business district." The first fire "destroyed two buildings and displaced four businesses." The second fire "displaced six businesses," and destroyed the "Lake Mall and an adjacent building." The details also noted that the "huge piles of charred rubble [were] gone and plans to rebuild were underway.” Today a new photography studio and art gallery neighbors a lakeside gazebo that welcomes people to downtown Lincoln. Across the street, a senior citizens’ apartment complex has risen from the site where the three-story mall once stood. From the smoke and destruction came a determination to rebuild something bigger and better.

Similarly, when the Lincoln News, the town’s only newspaper office, was completely destroyed by fire in November of 2009, owners refused to quit and released the next edition right on schedule by temporarily contracting with a publisher in another Maine community. The Ellsworth American was gracious enough to keep the presses rolling. Construction of a new office on the site of the old office began almost before the last ember died.

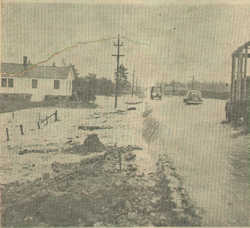

Lincoln Area Hit by Flood

Lincoln is a unique community with 13 lakes—14, if the part of Cold Stream Pond that lies within Lincoln’s borders is counted. With all that water, it is no surprise that the town has had flooding problems. The most destructive of the floods, however, had nothing to do with the lakes when the mettle of Lincoln residents was tested again on June 30, 1947. On that day, the Bangor Daily News reported that driving rains had caused heavy property and crop damage and that the rail line had been cut:

Following three hours of torrential rain, a flash flood swept down upon the Lincoln section late today causing heavy crop and property damage… Building up in the so-called Fish Hill section of Lincoln, a torrent of water swept down upon the south of the town of Lincoln, inundating stretches of the highway running to Enfield, washed out many acres of crops and caused widespread damage to private gardens and homes. The torrential downpour was accompanied by gale winds together with lightening flashes that struck at widely scattered parts of the community…

The damage from the flood was estimated in the thousands of dollars. Many of these damages occurred along the rail line, interrupting the only rail link between Vanceboro and Bangor. Passengers traveling south from Vanceboro or north from Bangor were halted at Lincoln and transported the rest of the way by bus and taxi. The washout also detoured the freight and passengers being transported from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Boston, Massachusetts.

According to newspaper reports, “Long-time residents of Lincoln said the storm was the worst in their memory”:

… at the height of the flash flood more than a foot of water poured across the highway and for a time motorists were stalled. As culverts proved inadequate to carry off the torrential flow, the highway base began to crumble under the pressure…

Mattanawcook Stream, within a few minutes, rose to higher than freshet proportions and gouged a great excavation out of the abutment of the bridge in the center of Lincoln. So great was the pressure under the bridge that the water burst through the road surface, leaving a hole a yard in diameter.

Despite “numerous and extensive” washouts, Lincoln town crews refused to quit, tracks were repaired within two days, and direct traffic was restored. (Bangor Daily News, July 2, 1947)

The First Hospital District

Trials and tribulations of a different type impacted Lincoln in the 1960s—caused not by the hand of Mother Nature, but by human intervention. The people of Lincoln called on their perseverance and civic pride to once again change loss into success.

On July 1, 1966, the Medicare Act was signed into law. As a result, hospitals were required to pass stringent inspections in order to receive compensation for Medicare patients. Two medical institutions served the Lincoln area at that time: the Workman Hospital and Lincoln Hospital—neither of which received certification to take Medicare patients.

A committee from the Health and Welfare Department in Augusta came to Lincoln in July of 1966, and suggested to Eugene Libby (owner of the Workman Hospital) and Dr. and Mrs. Albert Gulesian (owners of the Lincoln Hospital) that building a new hospital might be more feasible than trying to bring the two existing hospitals up to code.

Fundraiser for Lincoln's Hospital Administrative District, 1972

Lincoln Historical Society

Concerned members of the community met on August 16, 1966, to establish a hospital district. A 50-bed hospital was planned at a cost of $1,250,000—half of which would be funded by a federal Hill-Burton grant to improve hospital technology. The remaining funds for the hospital had to be raised by the townspeople of the pending hospital district. A group from each town met to organize their own fundraising. Many people canvassed the area asking for donations.

It took six years of planning, fundraising, and building for the dream of a modern healthcare facility to be realized. “The bill creating the first hospital administrative district in the state was ... signed [into law] by Governor Kenneth Curtis, and then went to referendum in the 16 towns” (Lincoln News, July 1967). The members of the 16 communities eventually approved Hospital Administrative District 1 by a vote of 1543 to 110. An Open House was held on May 19 and 20, 1973, to officially dedicate the hospital “built by the people for the people.” Plaques were put up in the new hospital to commemorate the donations of the citizens who contributed.

Today, the hospital is no longer Hospital Administrative District 1; it's a private, non-profit organization that functions as the center for primary, emergency, and acute care in Northern Penobscot County. The facility "provides dozens of services... including some of the most cutting-edge technologies in the state." In 2006, the hospital won national recognition from the Wellness Councils of America (WELCOA) for "promoting healthy living among employees" (www.pvhme.org).

Mill Closes

Lincoln and surrounding communities suffered another major blow in 1968 with the closure of the Eastern Fine Paper and Pulp Division of Standard Packaging Corporation.

The history of mills in Lincoln can be traced back to 1825 to a then fledgling sawmill operation. The charter of a mill with a real estate value of $75,000 was obtained in 1882. After several changes in ownership, the company was named Lincoln Pulp and Paper and began to manufacture “black ash” or sodium carbonate pulp. From 1899 to 1908, the mill built its reputation on the manufacturing of high-quality unbleached sulphite pulp and, in 1915, became known as the Katahdin Pulp and Paper Company, part of Eastern Manufacturing Company of Brewer referred to as Eastern Corporation.

In 1957, Eastern broke ground on a new $11 million dollar bleached Kraft mill on the site of the current mill; and, in 1958, the mill switched from manufacturing sulphite pulp to Kraft pulp (a more efficient process of turning wood into pulp). That same year Eastern Corporation and Standard Packaging Corporation merged, and the name changed to the Lincoln Division, Eastern Fine Paper and Pulp Division of Standard Packaging Corporation. In August 1961, pulp from the Lincoln Division traveled into outer space as a component of the shell of a NASA balloon satellite.

Construction of a new tissue mill (a mill that creates large rolls of thin paper that is then sent off to other manufacturing plants to be converted into a multitude of tissue products) was started in 1964. Then, on March 4, 1968, Standard Packaging announced that it was closing its plants in Brewer and Lincoln. The closing of the mills would cost 561 workers their jobs and impact nearly half of the town’s tax income.

Building of tissue mill, Lincoln, ca. 1966

Lincoln Historical Society

The tissue mill remained idle during the summer months, and then another milestone in the history of the Lincoln mills occurred: Premoid Corporation, a Massachusetts’ paper company, announced its interest in purchasing the Lincoln plant. There were conditions to the sale of the mill, however. The Corporation wanted the town to purchase $350,000 worth of bonds to help fund the mills, and the money had to be raised by June. On May 27, 1968, an offshoot of the Lincoln Development Corporation was formed, with the purpose of raising the money. Collection of the twenty-year bonds began on June 4, 1968, and took only 9 days! Numerous workers invested their severance pay from Eastern and used that money to buy bonds. Through the combined efforts of many, the mill was sold and operations began in August of that same year. It was through the prayers and the efforts of the people that the number one industry in the area continued to operate.

Lincoln Today

Paddling up the Penobscot River that borders Lincoln for 19 miles opens one’s eyes to the beauty of the area from which Mt. Katahdin can be seen in the distance. In the summer, loons are heard on any of Lincoln’s 13 lakes. In the fall, trees are ablaze with a myriad of colors before giving way to winter’s frozen snowmobile trails and ice-fishing huts. Spring gives birth to the many wild animals that frequent the hills, valleys, and woods that make up Lincoln’s 76.8 square miles: black bear, whitetail deer, moose, coyotes, bobcats, lynx, snowshoe hare, skunks, woodchucks, raccoons, fishers, otters, beavers, porcupines, squirrels, chipmunks, wild turkeys, eagles, turtles—the list goes on and on.

Those wishing to arrive in Lincoln today need only follow the Interstate 55 miles north from Bangor to Exit 227. When they do, they will still find a spirit of dogged perseverance among the more than 5,600 residents who take tremendous pride in their small town—residents who truly believe Maine’s motto, “The way life should be!”